Mar 10, 2025

Coalition looks for public help to transform the 'Black East Side'

Originally posted in the Buffalo News on March 10, 2025.

African Americans in Buffalo live in neighborhoods where employment opportunities are fewer, housing stock is of worse quality, neighborhoods are less walkable and there is less access to healthy food.

That’s a glimpse of what it’s like for many Black residents in the city, according to the University at Buffalo’s Community Health Equity Research Institute and its Center for Urban Studies.

But a pilot program − the East Side Neighborhood Transformation project – has been developed by a coalition of UB planners and researchers, community groups, residents and activists to transform the “Black East Side” into neighborhoods that support residents’ mental, social and physical well-being, organizers say. Otherwise, health inequities and underdeveloped Black neighborhoods will persist.

The target neighborhood for the East Side pilot project is located in the northern area of the Broadway-Fillmore neighborhood. Defined more precisely as U.S. Census tract 166, it is bounded by Broadway Avenue on the south, Fillmore Avenue to the east, Genesee Street on the west and Best Street to the north.

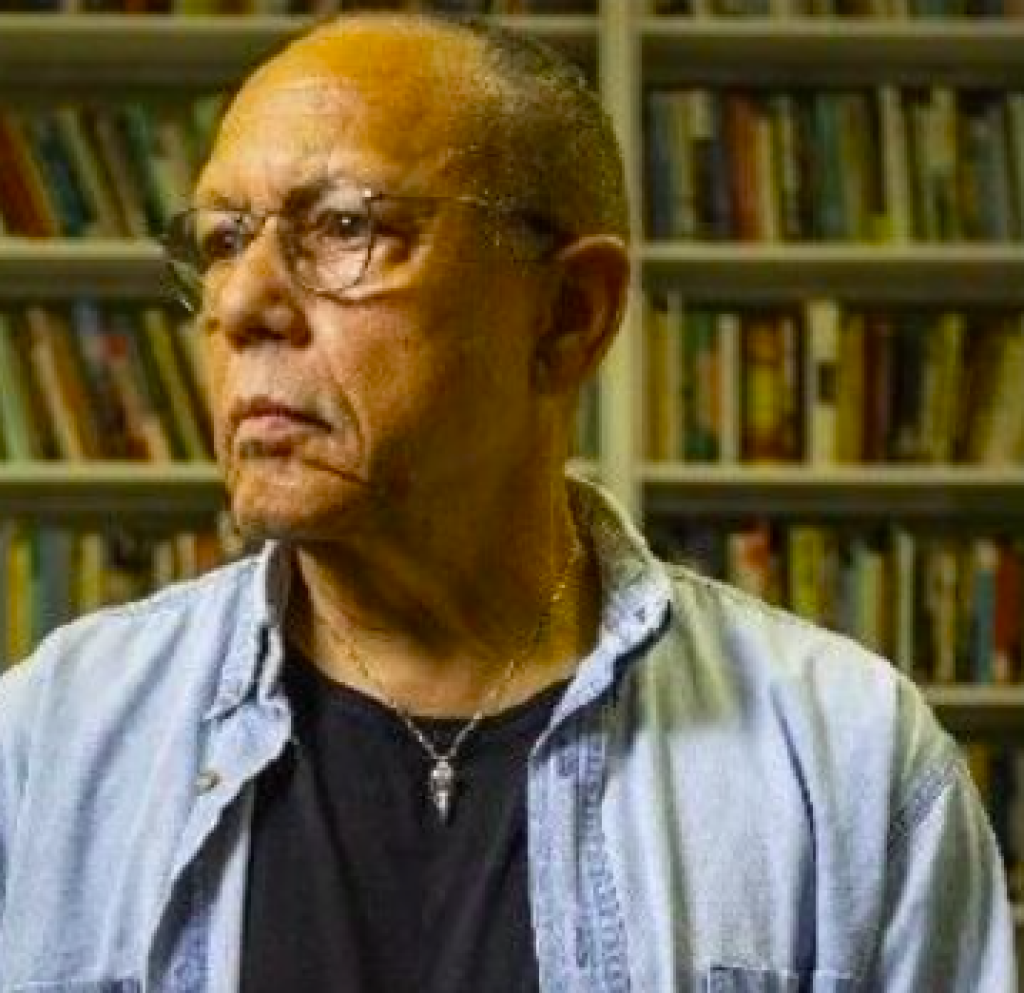

If the pilot plan succeeds on a small scale, the model will be expanded to other neighborhoods on the East Side and underdeveloped communities throughout Buffalo and Erie County, said Henry-Louis Taylor Jr., founding director of UB’s Center for Urban Studies at the School of Architecture and Planning. He is also the associate director of the Community Health Equity Research Institute at the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

Taylor will explain why the site was selected and give a brief overview of the project at a public meeting from 6 to 8 p.m. Monday at the King Urban Life Center, 938 Genesee St.

Elizabeth Triggs, 76, lives in the neighborhood and is expecting the pilot program to help neighbors and the community, but it will take all the stakeholders working together, she said.“We’re looking for hope, and we know there’s hope. I know there’s hope,” she said. “We need to start building these communities up. I think it’s a good start. But you know what? The community has to start doing a little better, too.”

Triggs was among a team of community members who provided their thoughts and ideas to the project, said Pastor James Giles of Back to Basics Outreach Ministries and executive director of the King Urban Life Center.

“We wanted to empower the residents, really make them feel like they’re responsible, and it’s their neighborhood and they’re responsible for exacting the change,” he said.

During Monday’s session Giles will discuss a mini-grant program. “We’ve made a lot of progress, but there’s still a lot of work still to be done,” said the Rev. George F. Nicholas, chief executive officer of the Buffalo Center for Health Equity and pastor of Lincoln Memorial United Methodist Church. Nicholas is the moderator for the event. He said with Buffalo getting ready for a mayoral election, this could be a good time for growth and new ideas.

“With the advent of new leadership that’s going to emerge in the city, I think there’s a great opportunity to kind of change how we do things … because what we’ve done really hasn’t helped those who need the help the most,” Nicholas said.

Little to no change, or worse

Taylor described Buffalo’s “Black East Side” as east of Main Street with the exception of South Buffalo. It’s where 75% to 80% of the city’s African American population lives. Most residents there pay more than 30% of their income on rent, with a significant number paying 50% or more, according to UB’s Center for Urban Studies. What’s more, African Americans in Buffalo have made very little economic progress over a period of some 30 years, Taylor said, defining that progress as the “movement toward transformation of underdeveloped neighborhoods into great places to live, work, play and raise a family.”

In 1990, for instance, the average household income for Black residents was around $39,000. Thirty years later, it was only $42,000. The home ownership rates were 33% in 1990 and 32% in 2020, while the poverty rate dropped slightly from around 38% to 35%. And the physical conditions inside the neighborhoods had actually worsened over the same time frame, Taylor said.

“For the majority of Black people, there have been no significant socioeconomic changes in their lives. The median household incomes, the poverty rates, the unemployment rates, were essentially the same. Homeownership rates barely moved,” Taylor told The Buffalo News.

Still, the East Side is a complex and diverse community with mixed income neighborhoods, he said.

“Most of the neighborhoods will have anywhere from 15 to 20% of the population making $75,000 or more. So, the idea that the East Side is a community with nothing but poverty is not true,” he said.

The median household income for Black families is $36,000 per year.

“But to forget that other income groups are residing in these spaces is to make a mistake, and most of the neighborhoods in which Blacks are the majority, there are also whites and Asians and Puerto Ricans living inside these neighborhoods as well,” he said.

Development zones

The transformation pilot project for the East Side calls for three neighborhood development zones: the People Zone, the Housing Zone and the Neighborhood Zone.

The People Zone will focus on initiatives that promote community control of the neighborhood, education and skills training, youth development and abolishing neighborhood health inequities.

A neighborhood council of appointed and elected members will oversee and guide the community’s growth and development. Neighborhood residents will comprise 70% of the members. Organizers also plan to establish a community land trust − which acquires and places land under community control − to obtain residential, commercial, vacant and abandoned properties for the community’s benefit.

Another aim is to have every neighborhood child reading at or above their appropriate grade level and develop innovative on-the-job training programs to develop literacy and work skills. Year-round youth development activities − including violence prevention, recreation, as well as leadership, cultural and work-related activities – will be tied to neighborhood development and problem-solving.

The People Zone also will focus on abolishing neighborhood health inequities, the most pressing problem facing Blacks in Buffalo, organizers said.

“We focus on people, because they will be the engines that drive everything, and we want to be able to build capacity, but we also recognize that people have a whole range of individual problems and complexities that they face. So we want to be able to tackle them concurrently,” Taylor said.

The Housing Zone will focus on repairing rental housing and improving the rates of property ownership. The goal is to improve housing security and protect the neighborhood from developers and speculators. Another goal is to lower rents to about 20% of a household’s income and improve housing quality by establishing a minimum level of housing quality that all rental units must sustain.

“Housing is the anchor for everything, and we know that in a complex, diverse community, you have to develop a whole range of different housing options,” Taylor said.

“The real issue is, how do we improve the actually existing housing in which people live,” he added.

And the Neighborhood Zone will help bolster the neighborhood’s unhealthy, run-down, desolate and forgotten visual image, planners say. The intent is to transform the East Side into a healthy, walkable community filled with trees, shrubbery, flowers and natural amenities.

It involves reconstructing the physical environment, including fixing the sidewalks, curbs and streets, beautifying vacant lots and abandoned structures and creating a vibrant green infrastructure throughout the neighborhood.

Monday’s event is free and open to the public. Registration is required via UB’s website.